Introduction to the Reward System

The brain's reward system evolved to reinforce behaviors essential to survival, including eating. This system operates through sophisticated neurobiological mechanisms involving dopamine—a neurotransmitter that plays a central role in reward processing, motivation, and learning.

However, in contemporary food environments with abundant access to highly palatable foods engineered for maximum sensory appeal, this ancient reward system can become engaged in ways that extend far beyond nutritional requirements. Understanding the neurobiological mechanisms of the dopamine reward circuit provides crucial insight into how eating behavior can become motivated by reward-seeking independent of metabolic needs.

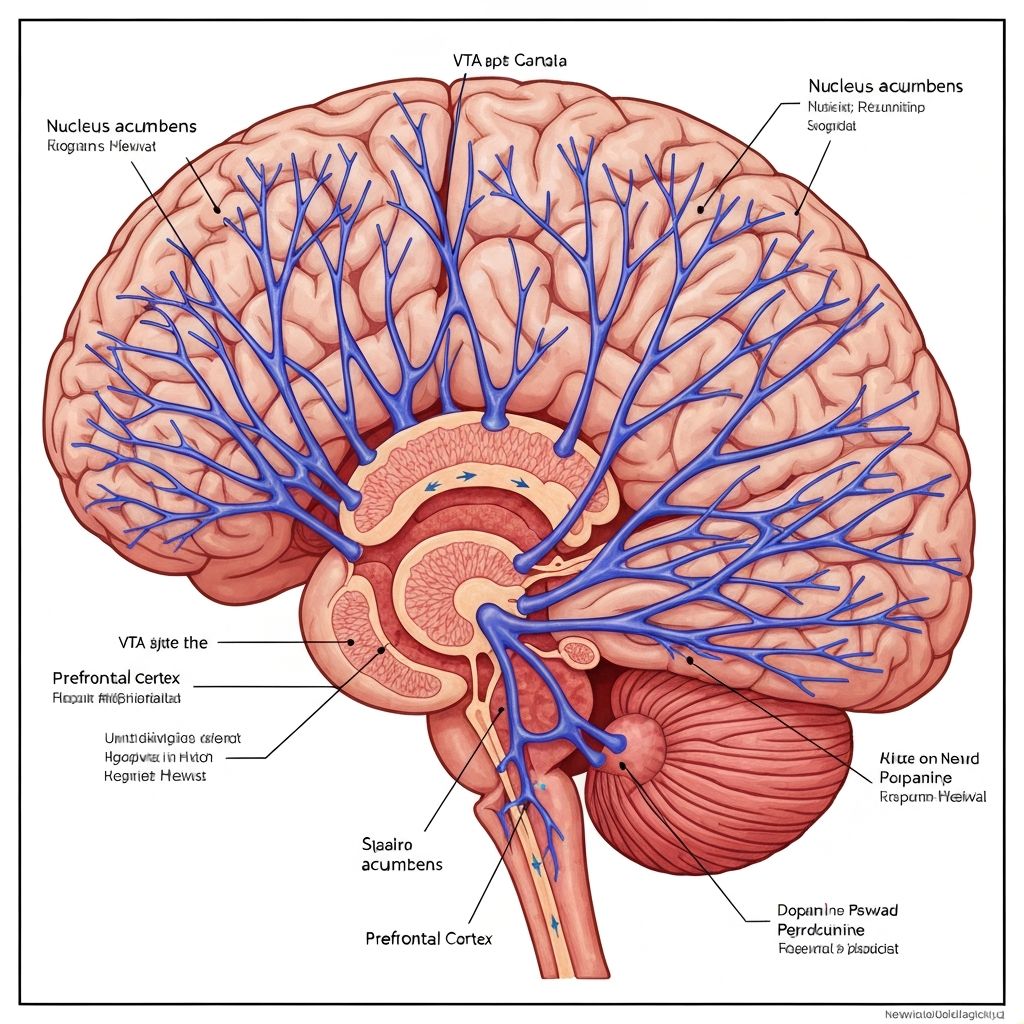

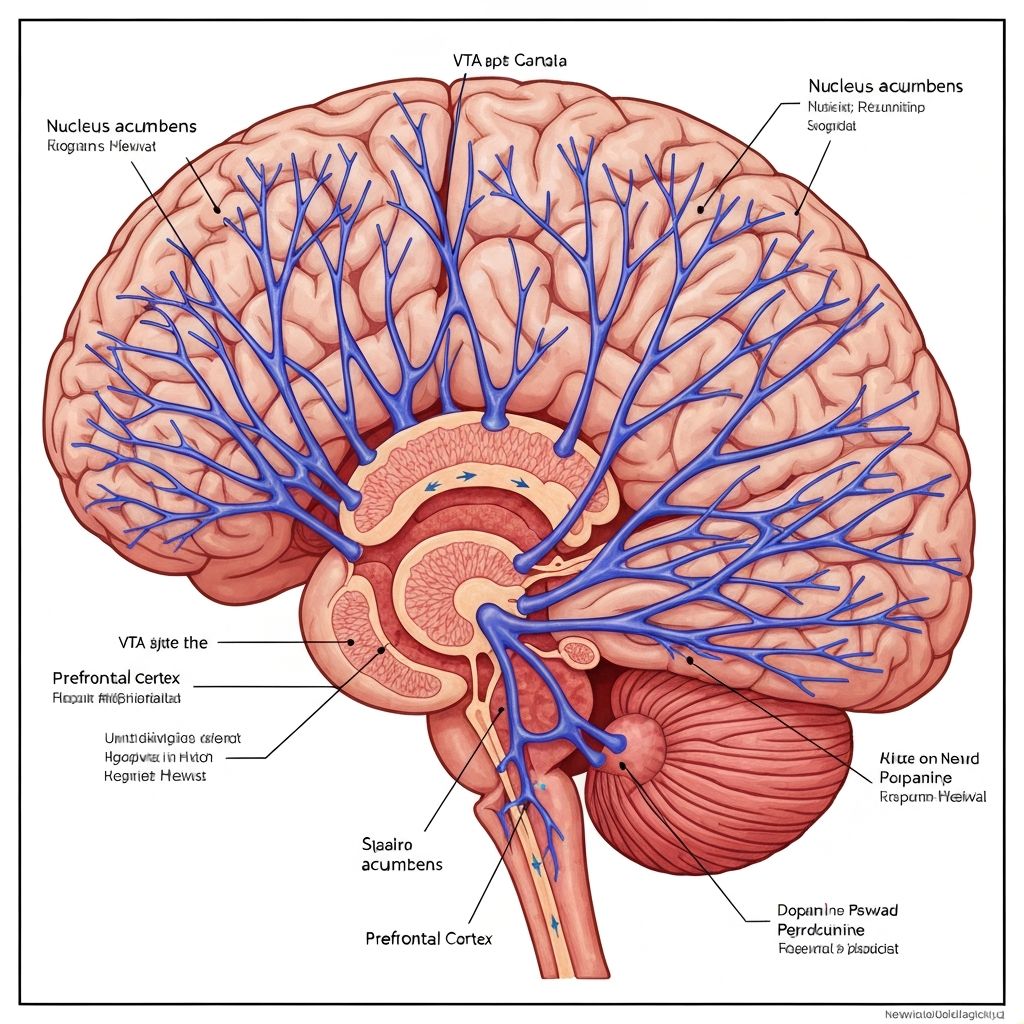

The Ventral Tegmental Area and Nucleus Accumbens

The ventral tegmental area (VTA) and nucleus accumbens form the core of the brain's reward system. Dopamine neurons in the VTA project to the nucleus accumbens, where dopamine release is associated with the experience of reward or the anticipation of reward.

Neuroimaging studies demonstrate that presentation of food images or the smell of food activates the nucleus accumbens through dopamine release, even in the absence of actual food consumption. This means that environmental cues associated with food—visual appearance, aroma, context—can activate reward circuitry through learned associations.

The strength of dopamine responses in the nucleus accumbens correlates with the subjective intensity of food cravings and desire to consume, illustrating the direct link between neural reward activation and behavioral motivation toward food consumption.

Hedonic vs Homeostatic Eating

Eating motivated by the brain's reward system is termed hedonic eating—consumption driven by pleasure and reward rather than metabolic need. This contrasts with homeostatic eating, which is motivated by physiological hunger signals and serves to maintain energy balance.

While some overlap exists between these systems, hedonic eating can proceed independently of homeostatic hunger signals. This explains the common observation of consuming additional food motivated by reward despite having adequate caloric intake and absence of physiological hunger.

The reinforcing properties of food—its taste, texture, aroma—directly engage dopamine reward pathways. Foods engineered for maximum palatability demonstrate particularly strong activation of reward circuitry, explaining their powerful motivational effects on eating behavior.

Anticipation and Cue-Induced Craving

A crucial aspect of dopamine reward system function is its role in anticipatory reward. Dopamine is released not only during consumption of a rewarding stimulus but also during anticipation of that reward. Environmental cues associated with food—a particular restaurant, food advertisements, the smell of cooking—can trigger dopamine release and craving through learned associations.

This anticipatory function creates a system where cues in the environment activate motivation to seek food reward even in the absence of physiological hunger. Over time, through repeated pairings, increasingly subtle environmental cues become capable of triggering reward system activation and food-seeking behavior.

This mechanism explains how individuals may experience strong food cravings in response to contextual triggers—passing a favorite restaurant, viewing food images—that activate learned associations with food reward through dopamine system engagement.

Prefrontal Cortex and Impulse Control

The prefrontal cortex provides top-down control over reward system activation, allowing deliberate decision-making to override reward-driven impulses. However, the power of prefrontal control over reward motivation shows individual variation and is susceptible to factors like stress, fatigue, and emotional state.

When prefrontal function is compromised—through stress, sleep deprivation, or intense emotional arousal—the relative influence of reward system activation on behavior increases. This creates conditions where reward-driven eating becomes more likely to proceed without the moderating influence of deliberate, executive decision-making.

The balance between reward system motivation and prefrontal control represents a critical factor in whether reward-activated eating behavior will occur. Understanding this balance illuminates why emotional states that impair prefrontal function frequently accompany patterns of reward-driven eating.

Learning and Memory in the Reward System

The dopamine reward system is intimately involved in learning and memory formation. Dopamine release during rewarding experiences strengthens neural connections, encoding memories of the experience and associated environmental contexts.

These learned associations persist over time and can be reactivated by similar environmental cues, explaining why past eating experiences influence current food motivation. A food or context that previously provided reward continues to activate dopamine responses when encountered again, even after considerable time intervals.

This learning mechanism has evolutionary advantages for survival, allowing organisms to identify and seek rewarding resources. However, in modern food environments, this same learning mechanism can encode strong associations between food cues and reward, contributing to powerful motivational drives toward food consumption.

Neurobiological Basis of Food Preferences

Individual differences in food preferences reflect differences in reward system sensitivity to different food types and learned associations from personal food history. Repeated consumption of particular foods strengthens dopamine associations with those foods, increasing their reward value.

Cultural food traditions similarly operate through dopamine learning mechanisms—foods central to childhood experiences and cultural practices become increasingly valued through repeated pairing with reward and social contexts. This explains why comfort foods often reflect cultural and personal food histories rather than universal food preferences.

The neurobiological reward system responses to food are modifiable through experience, suggesting that changing patterns of food exposure and consumption can gradually alter the brain's reward responses to particular foods over time.

Conclusion: Understanding Reward-Driven Eating

The dopamine reward circuit represents a sophisticated neurobiological system that evolved to reinforce survival-relevant behaviors but operates in modern food environments in ways that frequently extend beyond metabolic requirements. Understanding this system helps explain the neurobiological basis of hedonic eating motivated by reward rather than hunger.

Environmental food cues, learned associations, and the palatability of engineered foods all engage this reward system through dopamine mechanisms. The interaction between reward motivation and prefrontal control influences whether such activation translates into actual eating behavior.

This knowledge provides foundation for understanding how emotion-driven eating represents not individual weakness but engagement of ancient neural systems in contemporary environmental contexts.

Educational context: This article presents research on neurobiological mechanisms. It provides scientific information without offering personal recommendations or medical advice. Understanding these mechanisms supports informed appreciation of the complexity of eating behavior.