The Stress Response System

The human body possesses a sophisticated stress response system designed to mobilize resources in response to perceived threats. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis represents the primary endocrine system coordinating this response, releasing hormones including cortisol that prepare the body for action.

While this system provided survival advantages in ancestral environments characterized by acute physical threats, contemporary stress often persists over extended periods without corresponding physical resolution. This chronic activation of the stress response produces prolonged elevation of stress hormones, with significant consequences for appetite regulation and food consumption behavior.

Understanding the neurobiological connections between stress, stress hormones, and eating behavior illuminates the mechanisms through which psychological stress becomes translated into altered eating patterns.

Cortisol and Appetite Regulation

Cortisol, the primary stress hormone, influences appetite through multiple mechanisms. Acute stress typically produces cortisol elevation that temporarily suppresses appetite—an adaptive response in situations requiring immediate action. However, chronic stress results in sustained cortisol elevation that often leads to stress-induced appetite increase.

The mechanisms underlying this shift from acute suppression to chronic elevation effects on appetite remain subject of ongoing research. Evidence suggests that chronically elevated cortisol affects glucose metabolism, increases preference for calorie-dense foods, and influences central appetite-regulating systems in the hypothalamus.

Additionally, elevated cortisol can increase insulin secretion and promote insulin resistance, creating metabolic conditions that promote the sensation of hunger and desire for high-calorie foods.

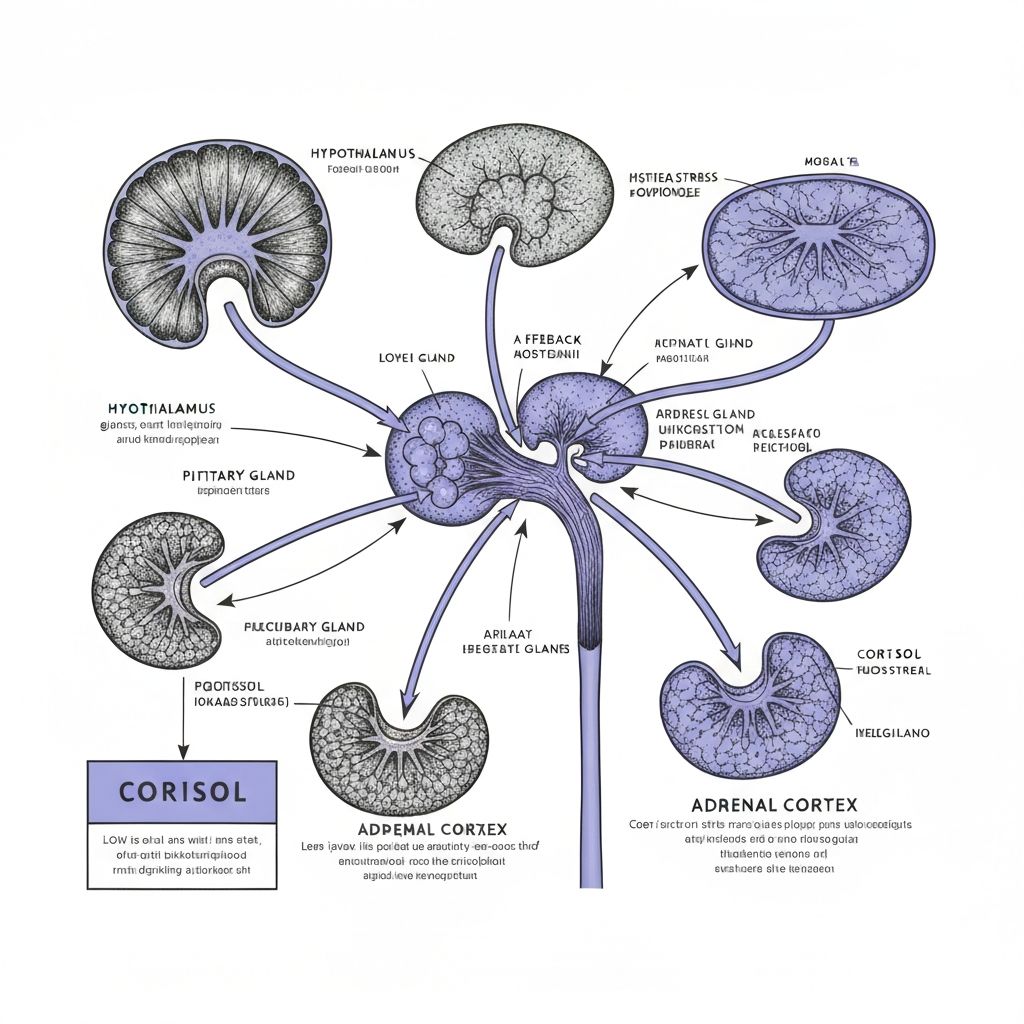

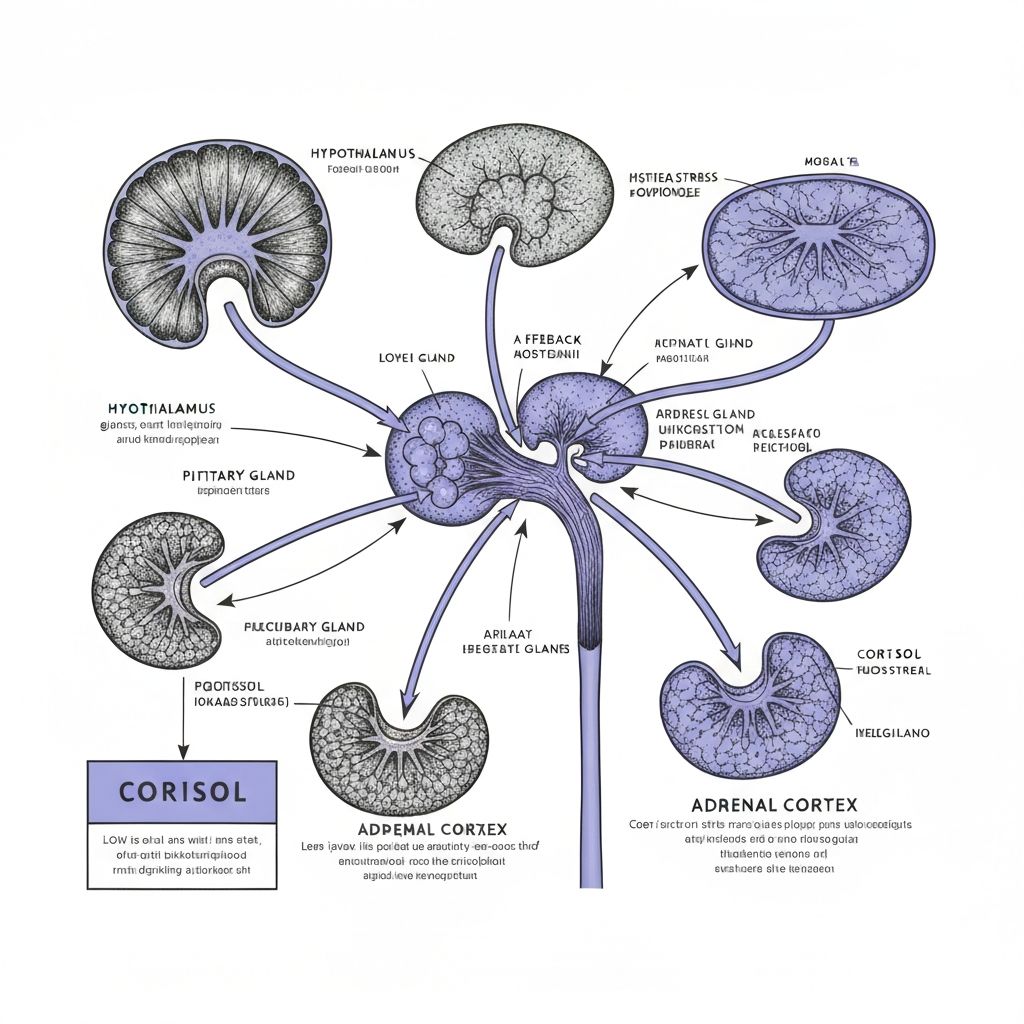

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis

The HPA axis operates as a feedback loop: the hypothalamus releases corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), which stimulates the pituitary gland to release adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which in turn stimulates cortisol release from the adrenal cortex.

The hypothalamus also contains hunger and satiety regulating circuits. Chronic stress-induced HPA axis activation can dysregulate these appetite-controlling mechanisms, altering the balance between hunger and satiety signaling.

This neuroendocrine dysregulation explains how psychological stress becomes translated into altered appetite and increased motivation toward food consumption. The same brain region coordinating stress response also controls appetite regulation, allowing stress to directly influence feeding behavior.

Chronic Stress and Metabolic Changes

Chronic elevation of cortisol produces metabolic changes that promote increased food intake, particularly consumption of calorie-dense foods. Elevated cortisol increases glucose availability in the bloodstream to provide energy for the stress response, which paradoxically can increase hunger signals.

Additionally, chronic cortisol elevation promotes visceral fat accumulation and can contribute to insulin resistance—metabolic conditions associated with increased hunger and difficulty with appetite regulation. These metabolic changes represent adaptations to chronic stress that, in modern food environments, often result in increased total food intake and weight gain.

The preference for high-calorie foods during stress reflects both direct hormonal influences on food choice and the rewarding properties of calorie-dense foods in promoting dopamine system activation—a mechanism through which stress-induced changes in reward system function influence eating behavior.

Sleep Disruption and Appetite Dysregulation

Stress frequently disrupts sleep, and sleep disruption independently influences appetite regulation through effects on ghrelin and leptin—the hormones regulating hunger and satiety. Sleep deprivation elevates ghrelin levels and reduces leptin effectiveness, creating a neurobiological state that promotes increased food intake.

The combination of stress-induced cortisol elevation and stress-related sleep disruption produces compounding effects on appetite regulation. Both independently promote increased hunger and food intake, and together they create particularly strong conditions for appetite dysregulation.

This explains why individuals experiencing chronic stress frequently report both increased appetite and specific preference for comfort foods—both the direct hormonal effects of stress and the indirect effects through sleep disruption converge to promote altered eating patterns.

Prefrontal Cortex Impairment Under Stress

Chronic stress impairs prefrontal cortex function, reducing the brain's capacity for deliberate decision-making and impulse control. This neuroendocrine effect has direct implications for food consumption behavior, as prefrontal function normally provides top-down regulation over reward-driven impulses, including food-seeking behavior.

When prefrontal function is compromised by stress, the influence of reward-driven motivations on behavior increases relative to deliberate, executive control. This creates conditions where appetite-related impulses become more likely to translate into actual eating behavior without the moderating influence of conscious decision-making.

This mechanism explains the common observation that periods of stress correlate with reduced ability to resist food cravings and increased consumption of preferred foods—the neurobiological basis reflects reduced prefrontal control over reward-seeking behavior under conditions of stress.

Individual Differences in Stress-Related Eating

While the physiological mechanisms linking stress to appetite dysregulation apply universally, individuals show considerable variation in whether stress produces increased or decreased eating. These individual differences likely reflect genetic variation in stress hormone responsivity, learned associations between food and emotional regulation, and psychological coping strategies.

Some individuals, designated stress-induced eaters, show increased food intake during stress, while others show decreased intake. Research suggests that stress-induced eating patterns reflect learned associations wherein food consumption has been used to regulate distress, creating conditioned responses whereby stress triggers food-seeking behavior.

Understanding these individual differences illuminates how stress-related eating reflects not universal stress physiology alone but rather the interaction between stress physiology and individual history of using food for emotional regulation.

Conclusion: Stress and Appetite Pathways

The connection between stress and altered eating behavior reflects multiple converging physiological mechanisms: HPA axis dysregulation, cortisol effects on metabolism and appetite regulation, sleep disruption, and impaired prefrontal control over reward-driven behavior. Together, these mechanisms create conditions promoting increased food intake during periods of psychological stress.

Understanding these endocrine and neurobiological mechanisms reveals how emotional states become translated into altered eating through physiological pathways. The stress-induced eating pattern represents engagement of these biological systems rather than psychological weakness or lack of discipline.

This knowledge provides foundation for understanding the neurobiological basis of stress-related changes in eating behavior and their role in broader patterns of emotion-driven food consumption.

Educational context: This article presents research on stress physiology and appetite mechanisms. It provides scientific information without offering personal recommendations or medical advice. Understanding these mechanisms supports informed appreciation of the complexity of stress-related eating behavior.